After three years of economic decline that depleted Latin America’s GDP of $1.7 trillion, depleting the region appears poised for a rebound in 2017. Economic hardship and a surge of civic consciousness have convinced millions of South American voters to reject populism and the record levels of corruption realized during the commodity super-cycle that ran from 2005-2013. In Argentina and Brazil, new governments have embraced pro-investor reforms; in Ecuador and Bolivia, voters denied their presidents another term in national plebiscites; Venezuelans elected an opposition-controlled Congress; and Peruvians chose a technocrat over a populist for president.

The political tide has clearly changed, but don’t hold your breath for a sudden positive economic rebound. At the start of this new economic cycle, the global environment is far less accommodating than at a similar point in 2005. U.S. interest rates are forecast to rise steadily after 15 years of historically loose monetary policy. Free-trade agreements, which helped portions of Latin America achieve strong growth, will be more difficult to strike with growing isolation and protectionism on both sides of the Atlantic. China’s debt-driven infrastructure spending spree is over, so industrial metal prices will struggle to return to their 2012 highs. A re-emerging U.S. energy superpower (nearly 90 percent energy independent) coupled with declining global oil demand will keep oil prices stagnant while international prices for liquefied natural gas will decline.

Without a commodity boom to rescue Latin America, the region must rise the old-fashioned way — by cutting waste and graft from government and raising productivity through smart reforms.

The commodity boom afforded Latin American governments for the first time in a generation the ability to finance new infrastructure. Over $1 trillion was invested. However, much of it was wasted or misdirected through public coffers, though some of it worked, especially when spent by private concerns. Latin America today has impressive cellular infrastructure, a few dozen world-class ports and airports, improved railways and roads and in a several countries much improved electricity grids.

But market reform is a continuous process and an incessantly challenging one. Latin America has much to do to catch up with other emerging markets, many of which kept reforming while South America, in particular, stood still for a decade.

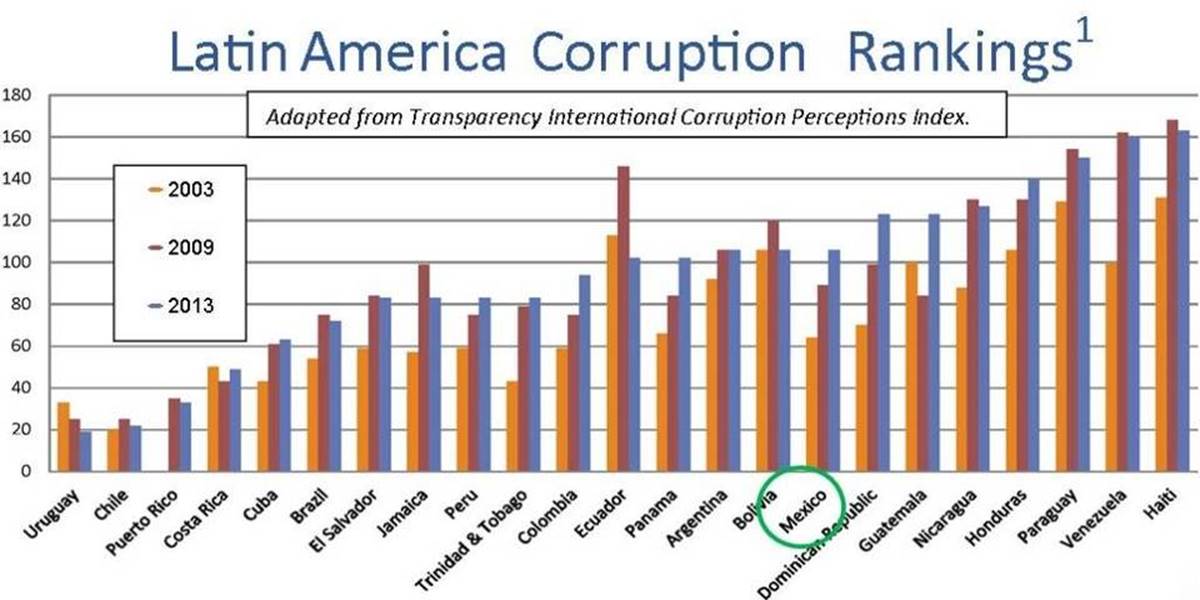

The region’s Achilles’ heel remains its weak rule of law. Until it is strengthened, politicians will continue to rob the region of its wealth and future, crime will continue to tax society and drive the boldest and brightest abroad, and investors will refuse to invest in creative ideas whose intellectual property cannot be protected. The remarkable battle between the judiciary and its former political masters in Brazil today is just the tip of the iceberg of change that all countries in the region must realize before a trusted legal system is constructed that protects lives, capital and property.

Latin America is now the fastest aging population in the world. The number of elderly in Latin America will triple as a share of the population by 2050 and represent almost one in five Latin Americans. The region can no longer afford to lose its bravest and brightest to emigration. Instead, Latin America must nurture its human capital by increasing access and transform its school system at the secondary, vocational and university levels into one that educates and trains its young people with employable technical skills and a heavy emphasis on STEM at the post-secondary level. Only then, will Latin America have the skill sets it needs to harness both its impressive natural resources and creative potential.

Latin America’s political leaders can no longer afford to tinker around the edges and wait for the ample commodity prices and domestic demographics to provide growth. Competing in a globalized world is no longer a choice but a necessity. Can Latin America compete? Only if the region’s political leaders immediately undertake bold institutional reforms, embrace transparency, and demonstrate political guile with the nativist naysayers among them.

Jerry Haar is a public policy fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington and a professor of management and international business at Florida International University. John Price is the managing director of AMI, an international consultancy focusing on Latin America. They are the co-editors of “Can Latin America Compete?”

View all articles by Jerry Haar.

This column originally appeared in The Miami Herald on January 4, 2017